[caption id="attachment_20808" align="alignright" width="300"]

Hurricane Katrina - Flooding in Venice, LA[/caption]

Last year was the tenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, the costliest hurricane in United States history. Since then, the major hurricane drought has continued, with 11 years and no major hurricanes, defined as Category 3, 4 and 5. In fact, in the last seven years only four hurricanes have hit the U.S.,

a streak not seen since the nation began keeping hurricane statistics in 1851.

Still, the last 11 years have brought many lessons about hurricanes.

First, the strength of a hurricane isn’t the best predictor of its destructiveness. Flooding and storm surge

cause more death and damage than wind.

Hurricane Katrina, was only a Category 3, on a scale of 1 to 5,

when it made landfall in 2005.

Sandy, the second-most expensive, was

only a Category 1 when it came ashore in New Jersey.

Hurricane Patricia, which hit Mexico in 2015, was the second-strongest hurricane in recorded history. Yet its storm surge was small, and it landed in a rural area, so damage was limited.

Second, communication and transportation are key before, during and after a hurricane. After Hurricane Katrina, businesses had trouble communicating with employees and customers, according to a booklet by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council,

Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina: Preparing Your Institution for a Catastrophic Event.

Both land lines and cell towers were damaged. Mail was disrupted for a long time thereafter, so bill payments couldn’t get through and services got canceled as a result. Roads were washed out and infrastructure damaged so people couldn’t get to jobs or even evacuation centers. Once they were in evacuation centers, flooding and diverted transportation kept them from leaving.

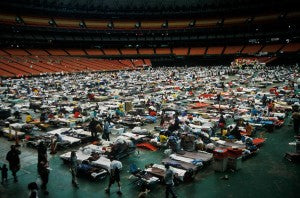

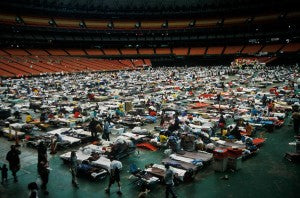

[caption id="attachment_20809" align="alignright" width="300"]

Inside the Superdome following Hurricane Katrina - via Tony's Huddle[/caption]

Take the Superdome, which became a symbol of the horror a hurricane can inflict. When the Superdome general manager agreed to open the building as an emergency shelter, it was originally intended to hold fewer than 1,000 patients with special medical needs for about two days,

according to a story in For the Win, a subsidiary of

USA Today.

It eventually held 30,000 people for almost a week. Debris, water, and destroyed transportation corridors kept food, medical supplies, and fuel from getting to New Orleans. Phone service, including 911, was almost nonexistent.

“When roads are flooded, washed out, blocked by trees and power lines, etc., it takes a while to get them back in order. That means you need to be prepared to get by for at least a few days

— and, much better, at least a couple of weeks

— on your own,”

wrote Glenn Reynolds, an editorial contributor to

USA Today, in a story about lessons from Katrina.

On the other hand, the owner of Liedenhelmer Banking Company in New Orleans closed the company’s plant and encouraged his employees to prepare their homes and evacuate, according to a an article from the

Federal Emergency Management Agency. The company also kept phone numbers and evacuation contact information for key employees. After the hurricane, all his employees were safe, though many suffered losses. He later arranged for a carpool service to take employees in shelters to and from work.

“What some of our folks faced and what they are still facing in their personal lives is heart-breaking. It is important to listen to the needs of employees,” he told FEMA.

Third, financial systems break down during a hurricane. After Katrina, power outages and overwhelmed backup servers left banks without computer access, including access to customers’ financial information,

according to Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina. In addition, some bank branches and ATMs were under water for weeks and others were severely damaged.

Keep cash in small bills in a short-term emergency kit, suggested Ann House, coordinator of the Personal Money Management Center at the University of Utah

Emergency managers fear the lack of recent hurricanes is making people complacent. Katrina and other recent hurricanes taught that preparing for hurricanes beforehand can reduce problems after.

"The farther we get from the last hurricane, the closer we get to the next one," National Hurricane Center spokesman Dennis Feltgen told

USA Today.

Hurricane Katrina - Flooding in Venice, LA[/caption]

Last year was the tenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, the costliest hurricane in United States history. Since then, the major hurricane drought has continued, with 11 years and no major hurricanes, defined as Category 3, 4 and 5. In fact, in the last seven years only four hurricanes have hit the U.S., a streak not seen since the nation began keeping hurricane statistics in 1851.

Still, the last 11 years have brought many lessons about hurricanes.

First, the strength of a hurricane isn’t the best predictor of its destructiveness. Flooding and storm surge cause more death and damage than wind.

Hurricane Katrina, was only a Category 3, on a scale of 1 to 5, when it made landfall in 2005. Sandy, the second-most expensive, was only a Category 1 when it came ashore in New Jersey.

Hurricane Patricia, which hit Mexico in 2015, was the second-strongest hurricane in recorded history. Yet its storm surge was small, and it landed in a rural area, so damage was limited.

Second, communication and transportation are key before, during and after a hurricane. After Hurricane Katrina, businesses had trouble communicating with employees and customers, according to a booklet by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina: Preparing Your Institution for a Catastrophic Event.

Both land lines and cell towers were damaged. Mail was disrupted for a long time thereafter, so bill payments couldn’t get through and services got canceled as a result. Roads were washed out and infrastructure damaged so people couldn’t get to jobs or even evacuation centers. Once they were in evacuation centers, flooding and diverted transportation kept them from leaving.

[caption id="attachment_20809" align="alignright" width="300"]

Hurricane Katrina - Flooding in Venice, LA[/caption]

Last year was the tenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, the costliest hurricane in United States history. Since then, the major hurricane drought has continued, with 11 years and no major hurricanes, defined as Category 3, 4 and 5. In fact, in the last seven years only four hurricanes have hit the U.S., a streak not seen since the nation began keeping hurricane statistics in 1851.

Still, the last 11 years have brought many lessons about hurricanes.

First, the strength of a hurricane isn’t the best predictor of its destructiveness. Flooding and storm surge cause more death and damage than wind.

Hurricane Katrina, was only a Category 3, on a scale of 1 to 5, when it made landfall in 2005. Sandy, the second-most expensive, was only a Category 1 when it came ashore in New Jersey.

Hurricane Patricia, which hit Mexico in 2015, was the second-strongest hurricane in recorded history. Yet its storm surge was small, and it landed in a rural area, so damage was limited.

Second, communication and transportation are key before, during and after a hurricane. After Hurricane Katrina, businesses had trouble communicating with employees and customers, according to a booklet by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina: Preparing Your Institution for a Catastrophic Event.

Both land lines and cell towers were damaged. Mail was disrupted for a long time thereafter, so bill payments couldn’t get through and services got canceled as a result. Roads were washed out and infrastructure damaged so people couldn’t get to jobs or even evacuation centers. Once they were in evacuation centers, flooding and diverted transportation kept them from leaving.

[caption id="attachment_20809" align="alignright" width="300"] Inside the Superdome following Hurricane Katrina - via Tony's Huddle[/caption]

Take the Superdome, which became a symbol of the horror a hurricane can inflict. When the Superdome general manager agreed to open the building as an emergency shelter, it was originally intended to hold fewer than 1,000 patients with special medical needs for about two days, according to a story in For the Win, a subsidiary of USA Today.

It eventually held 30,000 people for almost a week. Debris, water, and destroyed transportation corridors kept food, medical supplies, and fuel from getting to New Orleans. Phone service, including 911, was almost nonexistent.

“When roads are flooded, washed out, blocked by trees and power lines, etc., it takes a while to get them back in order. That means you need to be prepared to get by for at least a few days — and, much better, at least a couple of weeks — on your own,” wrote Glenn Reynolds, an editorial contributor to USA Today, in a story about lessons from Katrina.

On the other hand, the owner of Liedenhelmer Banking Company in New Orleans closed the company’s plant and encouraged his employees to prepare their homes and evacuate, according to a an article from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The company also kept phone numbers and evacuation contact information for key employees. After the hurricane, all his employees were safe, though many suffered losses. He later arranged for a carpool service to take employees in shelters to and from work.

“What some of our folks faced and what they are still facing in their personal lives is heart-breaking. It is important to listen to the needs of employees,” he told FEMA.

Third, financial systems break down during a hurricane. After Katrina, power outages and overwhelmed backup servers left banks without computer access, including access to customers’ financial information, according to Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina. In addition, some bank branches and ATMs were under water for weeks and others were severely damaged.

Keep cash in small bills in a short-term emergency kit, suggested Ann House, coordinator of the Personal Money Management Center at the University of Utah

Emergency managers fear the lack of recent hurricanes is making people complacent. Katrina and other recent hurricanes taught that preparing for hurricanes beforehand can reduce problems after.

"The farther we get from the last hurricane, the closer we get to the next one," National Hurricane Center spokesman Dennis Feltgen told USA Today.

Inside the Superdome following Hurricane Katrina - via Tony's Huddle[/caption]

Take the Superdome, which became a symbol of the horror a hurricane can inflict. When the Superdome general manager agreed to open the building as an emergency shelter, it was originally intended to hold fewer than 1,000 patients with special medical needs for about two days, according to a story in For the Win, a subsidiary of USA Today.

It eventually held 30,000 people for almost a week. Debris, water, and destroyed transportation corridors kept food, medical supplies, and fuel from getting to New Orleans. Phone service, including 911, was almost nonexistent.

“When roads are flooded, washed out, blocked by trees and power lines, etc., it takes a while to get them back in order. That means you need to be prepared to get by for at least a few days — and, much better, at least a couple of weeks — on your own,” wrote Glenn Reynolds, an editorial contributor to USA Today, in a story about lessons from Katrina.

On the other hand, the owner of Liedenhelmer Banking Company in New Orleans closed the company’s plant and encouraged his employees to prepare their homes and evacuate, according to a an article from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The company also kept phone numbers and evacuation contact information for key employees. After the hurricane, all his employees were safe, though many suffered losses. He later arranged for a carpool service to take employees in shelters to and from work.

“What some of our folks faced and what they are still facing in their personal lives is heart-breaking. It is important to listen to the needs of employees,” he told FEMA.

Third, financial systems break down during a hurricane. After Katrina, power outages and overwhelmed backup servers left banks without computer access, including access to customers’ financial information, according to Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina. In addition, some bank branches and ATMs were under water for weeks and others were severely damaged.

Keep cash in small bills in a short-term emergency kit, suggested Ann House, coordinator of the Personal Money Management Center at the University of Utah

Emergency managers fear the lack of recent hurricanes is making people complacent. Katrina and other recent hurricanes taught that preparing for hurricanes beforehand can reduce problems after.

"The farther we get from the last hurricane, the closer we get to the next one," National Hurricane Center spokesman Dennis Feltgen told USA Today.