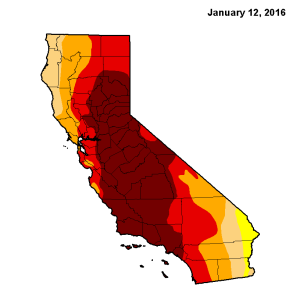

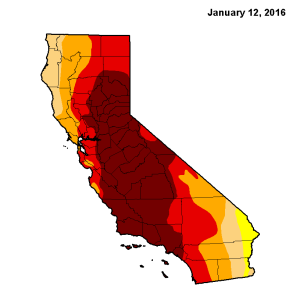

Look at these two pictures from the

United States Drought Monitor. This first is from a year ago. The entire state was in some level of drought, and almost half was in the highest level (exceptional drought – rust colored).

[caption id="attachment_21393" align="alignleft" width="300"]

California Drought as of January 12, 2016[/caption]

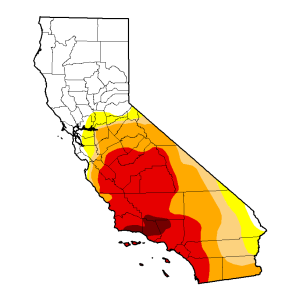

[caption id="attachment_21394" align="alignright" width="300"]

California Drought as of January 10, 2017[/caption]

Compare this year’s map. Everywhere north of Sacramento is drought-free. Only 2 percent of the state is in exceptional drought. Since January 1, Lake Tahoe’s water level has risen almost a foot – 33.6 billion gallons,

according to the National Weather Service.

The January storms that brought this remarkable turnaround also wreaked havoc. They:

Caused at least five deaths.

[caption id="attachment_21400" align="alignright" width="300"]

Pioneer Cabin Tree toppled in storm - image via Mercury News[/caption]

Toppled the "Pioneer Cabin" tree in Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Calif. The still-living giant sequoia had a tunnel, cut in the 1880s, that tourists could walk through.

Caused the Truckee River to overflow its banks, flooding Reno, Nev. suburbs and polluting drinking water in Storey County, Nev.

Closed ski resorts in California, Nevada, and Colorado when too much snow created

hazardous driving and avalanche conditions.

Dumped 35 inches of rain on California’s central coast. San Francisco

has already seen more precipitation in 2017 than it did in all of 2013.

Caused blizzard wind measuring 174 mph at Squaw Valley in the Sierra Nevada mountains on Jan. 8.

Forced evacuation of several northern California towns because of flooding.

Forced managers of the Yuba River to manually open a dam’s floodgates for the

first time in 10 years to prevent flooding in downtown Sacramento.

All of these events are is the product of a common weather phenomenon that drives between a third and a half of the precipitation in the western United States: atmospheric rivers.

Imagine a high-altitude fire hose. It’s not constant, but once it forms, it can stretch thousands of miles long (and tens to hundreds of miles wide). It can carry water vapor equivalent to 15 times the flow at the mouth of the Mississippi River,

according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As this flow interacts with a low-pressure storm system or runs into a mountain range, it brings a blast of precipitation that can last for days. Frequently, these systems follow each other.

One NOAA author called atmospheric rivers “drought busters,” because just a few such storms can break up droughts.

So this year’s series of atmospheric rivers have been a great boon to bone-dry California. Yet they haven’t brought as much rain to the southern part of the state. And they bring devastating flooding.

In 1861, rain started falling on Sacramento, Calif., on Christmas day, and stopped 43 days later,

according to a story from a NBC Bay Area affiliate. The state legislature had to move for six months because the city was submerged under 10 feet of water. California’s Central Valley – its bread basket – flooded, and the San Francisco Bay filled with so much fresh rainwater that its wildlife struggled, according to the story.

It was an extreme version of the most common atmospheric river to affect the western United States:

the Pineapple Express (no relation to the movie), nicknamed such because it often forms in the Pacific near Hawaii.

Another atmospheric river storm that began December 29, 1996,

dumped more than two feet of water in many northern California locations, killed two people and caused $1.6 billion in damages.

They’re not just confined to the west. An

atmospheric river was behind massive flooding in March 2016 in Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma.

And

two more are forecast to hit California this week.

Atmospheric rivers can bring all kinds of wild weather. So look around, think about what one might do to your area, and plan accordingly.

California Drought as of January 12, 2016[/caption]

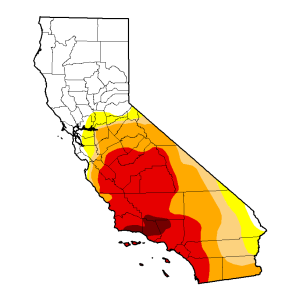

[caption id="attachment_21394" align="alignright" width="300"]

California Drought as of January 12, 2016[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_21394" align="alignright" width="300"] California Drought as of January 10, 2017[/caption]

Compare this year’s map. Everywhere north of Sacramento is drought-free. Only 2 percent of the state is in exceptional drought. Since January 1, Lake Tahoe’s water level has risen almost a foot – 33.6 billion gallons, according to the National Weather Service.

The January storms that brought this remarkable turnaround also wreaked havoc. They:

Caused at least five deaths.

[caption id="attachment_21400" align="alignright" width="300"]

California Drought as of January 10, 2017[/caption]

Compare this year’s map. Everywhere north of Sacramento is drought-free. Only 2 percent of the state is in exceptional drought. Since January 1, Lake Tahoe’s water level has risen almost a foot – 33.6 billion gallons, according to the National Weather Service.

The January storms that brought this remarkable turnaround also wreaked havoc. They:

Caused at least five deaths.

[caption id="attachment_21400" align="alignright" width="300"] Pioneer Cabin Tree toppled in storm - image via Mercury News[/caption]

Toppled the "Pioneer Cabin" tree in Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Calif. The still-living giant sequoia had a tunnel, cut in the 1880s, that tourists could walk through.

Caused the Truckee River to overflow its banks, flooding Reno, Nev. suburbs and polluting drinking water in Storey County, Nev.

Closed ski resorts in California, Nevada, and Colorado when too much snow created hazardous driving and avalanche conditions.

Dumped 35 inches of rain on California’s central coast. San Francisco has already seen more precipitation in 2017 than it did in all of 2013.

Caused blizzard wind measuring 174 mph at Squaw Valley in the Sierra Nevada mountains on Jan. 8.

Forced evacuation of several northern California towns because of flooding.

Forced managers of the Yuba River to manually open a dam’s floodgates for the first time in 10 years to prevent flooding in downtown Sacramento.

All of these events are is the product of a common weather phenomenon that drives between a third and a half of the precipitation in the western United States: atmospheric rivers.

Imagine a high-altitude fire hose. It’s not constant, but once it forms, it can stretch thousands of miles long (and tens to hundreds of miles wide). It can carry water vapor equivalent to 15 times the flow at the mouth of the Mississippi River, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As this flow interacts with a low-pressure storm system or runs into a mountain range, it brings a blast of precipitation that can last for days. Frequently, these systems follow each other.

One NOAA author called atmospheric rivers “drought busters,” because just a few such storms can break up droughts.

So this year’s series of atmospheric rivers have been a great boon to bone-dry California. Yet they haven’t brought as much rain to the southern part of the state. And they bring devastating flooding.

In 1861, rain started falling on Sacramento, Calif., on Christmas day, and stopped 43 days later, according to a story from a NBC Bay Area affiliate. The state legislature had to move for six months because the city was submerged under 10 feet of water. California’s Central Valley – its bread basket – flooded, and the San Francisco Bay filled with so much fresh rainwater that its wildlife struggled, according to the story.

It was an extreme version of the most common atmospheric river to affect the western United States: the Pineapple Express (no relation to the movie), nicknamed such because it often forms in the Pacific near Hawaii.

Another atmospheric river storm that began December 29, 1996, dumped more than two feet of water in many northern California locations, killed two people and caused $1.6 billion in damages.

They’re not just confined to the west. An atmospheric river was behind massive flooding in March 2016 in Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma.

And two more are forecast to hit California this week.

Atmospheric rivers can bring all kinds of wild weather. So look around, think about what one might do to your area, and plan accordingly.

Pioneer Cabin Tree toppled in storm - image via Mercury News[/caption]

Toppled the "Pioneer Cabin" tree in Calaveras Big Trees State Park, Calif. The still-living giant sequoia had a tunnel, cut in the 1880s, that tourists could walk through.

Caused the Truckee River to overflow its banks, flooding Reno, Nev. suburbs and polluting drinking water in Storey County, Nev.

Closed ski resorts in California, Nevada, and Colorado when too much snow created hazardous driving and avalanche conditions.

Dumped 35 inches of rain on California’s central coast. San Francisco has already seen more precipitation in 2017 than it did in all of 2013.

Caused blizzard wind measuring 174 mph at Squaw Valley in the Sierra Nevada mountains on Jan. 8.

Forced evacuation of several northern California towns because of flooding.

Forced managers of the Yuba River to manually open a dam’s floodgates for the first time in 10 years to prevent flooding in downtown Sacramento.

All of these events are is the product of a common weather phenomenon that drives between a third and a half of the precipitation in the western United States: atmospheric rivers.

Imagine a high-altitude fire hose. It’s not constant, but once it forms, it can stretch thousands of miles long (and tens to hundreds of miles wide). It can carry water vapor equivalent to 15 times the flow at the mouth of the Mississippi River, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As this flow interacts with a low-pressure storm system or runs into a mountain range, it brings a blast of precipitation that can last for days. Frequently, these systems follow each other.

One NOAA author called atmospheric rivers “drought busters,” because just a few such storms can break up droughts.

So this year’s series of atmospheric rivers have been a great boon to bone-dry California. Yet they haven’t brought as much rain to the southern part of the state. And they bring devastating flooding.

In 1861, rain started falling on Sacramento, Calif., on Christmas day, and stopped 43 days later, according to a story from a NBC Bay Area affiliate. The state legislature had to move for six months because the city was submerged under 10 feet of water. California’s Central Valley – its bread basket – flooded, and the San Francisco Bay filled with so much fresh rainwater that its wildlife struggled, according to the story.

It was an extreme version of the most common atmospheric river to affect the western United States: the Pineapple Express (no relation to the movie), nicknamed such because it often forms in the Pacific near Hawaii.

Another atmospheric river storm that began December 29, 1996, dumped more than two feet of water in many northern California locations, killed two people and caused $1.6 billion in damages.

They’re not just confined to the west. An atmospheric river was behind massive flooding in March 2016 in Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma.

And two more are forecast to hit California this week.

Atmospheric rivers can bring all kinds of wild weather. So look around, think about what one might do to your area, and plan accordingly.