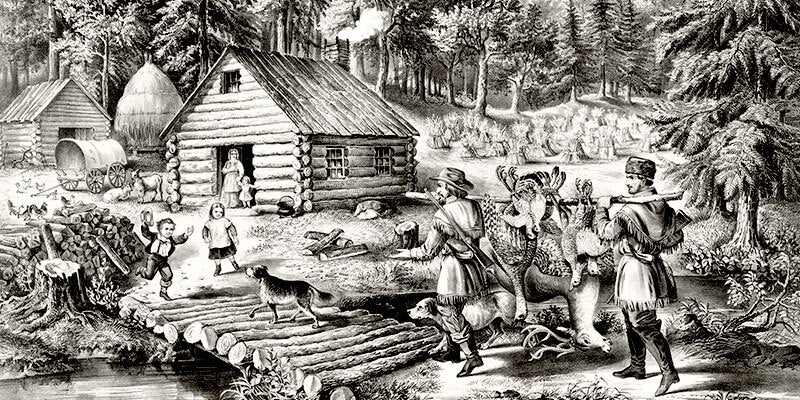

It’s no stretch to say that in terms of pure survival skill, the average American pioneer would put most of today’s preppers to shame.

In honor of Pioneer Day this weekend, we’re revealing the most vital skills pioneers knew that are lost to most Americans, and how to get started learning them.

1. Start a Farm...Or At Least Learn How.

Plenty of prep-minded folks have a garden. In fact, one in three American households currently grow food of some sort (thanks in part to COVID).

But the pioneers weren’t just gardeners, nearly all of them were farmers who lived off the land to a surprising degree. In the eighteenth century at least 90 percent of Americans were farmers (and most of the rest kept livestock and grew small crops). By the mid-nineteenth century—at the time of the great westward expansion—well over half of Americans were still farmers.

Today, things look a little different. Farmers and ranchers make up just 1.3% of the population, and it shows. Practically every one of us is a consumer in the truest sense of the word—wholly reliant on the industrial food system. And as COVID showed us, that system is fragile.

Homestead Farming

Even though many of us grow modest gardens, it wouldn’t be nearly enough to live off. In the event of a long-term food supply chain disruption, we’d be forced to rely almost completely on our emergency storage.

But what happens when food storage runs out?

We need look no further than our pioneer forbearers and homestead farming for the answer.

Here’s how to take the first steps to establishing your own homestead farm. It’s a decades-long process, but the people who’ve committed to it tell us they’d never take it back.

Calculate How Much Land You Need

There are lots of opinions on how much land you need to establish a homestead farm, but generally it’s a complex answer that depends on the size of your family and your individual needs. Some swear that five acres will do you. Others say that with livestock, you need at least 30 acres. And yet others claim you need as many as 17 acres a person to get by in relative comfort.

The folks at homesteading.com have calculated how much land a family of four would need to live for one year, and this is how they broke down their tabulations (read the entire article here):

Roof for energy production – A roof of at least 375 square feet (to continuously generate solar electricity for a year).

Garden space – .44 acres per person to maintain a vegetarian diet of 2,300 calories per day (that includes some fruits, vegetables, and grains) but no trees or wheat.

Eggs – 65 square feet for one year of eggs (a family of four eating 1,000 eggs a year would need 13 hens to fill their needs).

Pork – 207 square feet for one year of pork (three pigs can feed a family of four twice a week).

Dairy – 100 square feet minimum for dairy exclusively from goats (a single Nubian goat can produce 1,844 pounds of milk a year).

Wheat – Here’s the big one…one year of wheat requires 12,012 square feet, and even more if a portion goes to livestock.

Corn – One year of corn requires 2,640 square feet of land (adding more again if it's used for livestock feed).

Their total is 89,050 square feet, or about two acres. This would be a spare existence with an extremely small home, with no orchards (which take up about one acre for 70 trees), no cows, and no significant land for open grazing.

No matter how you cut it, a small family should plan on at least three acres and more likely five to 10. You’d be safer going for

Where to Get Land?

Gone are the days where oceans of free land that dot the countryside (the Homesteading Act was repealed in 1976 with provisions in Alaska till 1986). But that doesn’t mean free land no longer exists. You just have to look—and meet requirements—to get it.

As recently as this month, plenty of websites post free land notifications. They’ve recently popped up in places like Marne, Iowa; New Richland, Minnesota; Marquette, Kansas; and La Villa, Texas, to name just a few

2. Long-Term Shelter Building

Pioneer homesteaders were given land, but little else. There were no contractors to be found. As one early settler in Pella, Iowa put it, “there was not another family for fifty miles, no house, no nothing you might say.”

In conditions like these, pioneers were left to build their own homes with their own hands.

Their first shelter was often the wagon they’d traveled in, then a spare sod or log cabin, and if they had the means, eventually a homemade from milled lumber such as the I-Type house.

Build a Dugout from the Resources Available,Just Like the Pioneers

For long-term emergencies, fashioning shelter can be a lifesaver—second only to the air you breathe!

Here’s how the American pioneers built theirs, from a 1911 issue of Hunter-Trapper-Trader magazine. The author claims to have learned the technique from “the old days on the prairies of Iowa and Minnesota, by seeing the first settlers of land make them.”

“They are warm in the coldest weather, dry, if made right, in the wettest weather, and cool in the hottest weather,” he says. “Why they are not used more, I do not understand.”

Find the Right Spot

Look for a low hill, and begin digging out on the “lee” side—the portion sheltered from the wind. Rocky terrain does not favor a dugout; a nice sandy or sodden hill is best.

Bring the Right Tools

Our pioneer ancestors weren’t working the land with backhoes. They had simple tools: picks, shovels, axes, and breaking plows. Any of these will do for clearing soil for your cabin.

Measure Out the Right Size

Hunter-Trapper-Trader magazine claims a space 12-feet wide and 13-feet deep (156 square feet) will do for two men. This won’t be the entirety of the room—you’ll want to build out a little log cabin extending from the sod burrow. If you’re digging for a larger group, say a family of four, you might want to consider a couple side-by-side dugouts of about that size.

Dig Out Your Rooms

Now the work starts. According to the author, “Having selected your place, drift into the bank 12 feet by I3 feet wide and cut the bank or sides a little sloping instead of straight up and down, and throw the dirt out in front on the downhill side. Now build up in front log house fashion, or with sod and leaves, two openings for windows and one for a door. In the sod or logs, you can line the walls with rosin paper.

For a more detailed instructional on dugout building check out this video from My Bushcraft Story.

For a great instructional on log cabin building, check out this video series from the Bearded Carpenter.

3. Dig a Well

Lots of us today have emergency water storage (check out our article on water storage options if you need help getting started). But pioneers needed water sources—not supplements—to get them through the months and years they had to go it alone. If there weren’t lakes or rivers nearby (and often even if they were) our forbearers dug out wells with their own hands.

Digging a well is hard work, but not nearly as complicated as some may think. Here’s what you need to know to dig your own.

Find the Right Land

First you’ve got to find water, and this can be the hardest part.

We’ll leave arguments over the efficacy of “dousing” to others, and instead go to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for advice on locating groundwater:

"The landscape offers helpful clues. Shallow ground water is more likely to occur in larger quantities under valleys than under hills, because ground water obeys the law of gravity and flows downward just as surface water does. In arid regions the presence of "water-loving" plants is an indication of ground water at shallow depth. Any area where water shows up at the surface, in springs, seeps, swamps, or lakes, must have some ground water, though not necessarily in large quantity or of usable quality.

Rocks are the most valuable clues of all consolidated formations such as sandstone, limestone, or granite as well as for loose, unconsolidated sediments such as gravel or sand. An "'aquifer" is any body of rock that contains a usable supply of water. A good aquifer must be both porous enough to hold water and permeable enough to allow the continuous recharge of water to a well."

Dig a Shallow Well Yourself

Like we’ve said, digging a shallow well on your own property is far from impossible. Here's how to do it:

Check Local Law – To begin with, you’ll want to check the local laws governing well digging. Most states allow it if it’s on your own property, but there are some restrictions when it comes to depth. There are also areas where ground water is known to be contaminated—local officials can help identify these as well.

Check with Utility Companies – You’ll want to do this, especially if you live in a suburb or area that’s otherwise densely populated. You don’t want to hit any water, gas, telephone, or electric mains running under your property.

Test and Purify Your Water – Have your water tested for bacteria and chemicals on a regular basis. Use this guide to help set a schedule for testing. We also strongly suggest purifying all well water you consume with a large, high-quality filter like the Alexapure Pro.

The Basics Drilling a Shallow Well

a. Once you’ve picked your spot, use a hand auger (with extensions) to drill down. Make sure your hole goes straight Too many slants and angles will make it tough to insert your piping. Be sure to wear gloves to prevent splinters and blisters.

b. As you’re digging, keep a tarp or two near to deposit the soil you’ve dug. Make sure to keep track of the soil you remove first and last. The soil you take out last should be replaced first, and the first soil out should be replaced last. This will prevent surface chemicals from contaminating deeper dirt. Pay attention to the color of the sand as you make progress. If it changes, you’ll know you’re getting closer to water.

c. At about 10 to 20 feet down, you may start to get soggy soil coming up. Congratulations! You’ve hit water! Dig just a little deeper, and then on to the next phase of the project.

d. At this point, you need a four-inch PVC pipe that will act as your well wall. Place that into the hole. You’ll want three to four feet of pipe coming out of the ground (this is where the pump will be mounted).

e. With the pipe in the ground, tie a little nut to a the end of a length of string that’s longer than the well is deep. Lower the nut into the well. Once the slack goes out, you’ve hit water. Lower the nut to the bottom of the well. Pull it out and you can measure the entire depth of the well as well as the depth of the water.

f. Drill many small holes into the portion of your four-inch PVC pipe (the well wall) will be in direct contact with water. This hole allows the water to seep in. Cap the bottom of the pipe.

Note: The glued joints of your PVC pipes are the most vulnerable points. Make sure to attach them securely—if they come loose the well can become irreparably damaged or contaminated.

g. Now comes the draw pipe. Cut a length of 1 ¼ inch PVC pipe to about one foot shorter than the well depth. Add a foot valve to the bottom. This allows water into the well, but not out.

h. Prime your pump, then temporarily attach it to the top of the draw pipe. See if you can pump water up (this may take a while). If you can, you’re on your way to completing the project. If not, you may soon find yourself digging another hole.

i. Refill the hole around the well wall. Start with pea gravel and then add the extracted soil. Compact the soil as much as possible as you go.

j. Use a PVC adaptor to connect your pump to the draw pipe and attach the pump to the well pipe. For more on how to do this, check this video (go to time mark 8:38).

k. Pour concrete around the footing of the pipe.

A special thank you to YouTubers Specific Love Creations, OGB, TigerCreekFarm, and EmergencyWaterWell.com for their excellent video tutorials on this subject. Check them all out here for more help digging your well.

This Is Just the Beginning…

And that’s just the beginning. We didn't even get into woodworking, weaving, butchering and curing meat, making your own flour, or creating your own light sources. There’s so much to learn.

Happy Pioneer Day and stay prepped!

Image Credits:

"Hand Plow" by woychukb is licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

"66-09 08 Wonders digging" by stosturms is licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

"(animated stereo) A 19th Century Sod House in Kansas" by Thiophene_Guy is licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

2 comments

Sara Bailey

God Bless you I hope I can get a better head start to help my kids and just n case others too.

Sara

I am interested in all that you can offer. Best way of contacting is phone or text and VM. Thanks GOD BLESS